On frustration: Perceived vs actual ability

You’re busy having a great time. You’re learning something new. It’s going well, until… bam, you’re stuck. Frustration boils over. You’re close to quitting. Hopefully, your motivation outweighs the frustration. Hopefully, you persist.

By its very definition, frustration is a negative emotion.

the feeling of being upset or annoyed as a result of being unable to achieve something

But while frustration feels bad, it’s actually a good sign. Not only does it give you a signal of intent (how motivated are you to overcome the hurdle causing the frustration) but it also gives you a signal to change. Let’s talk about the latter.

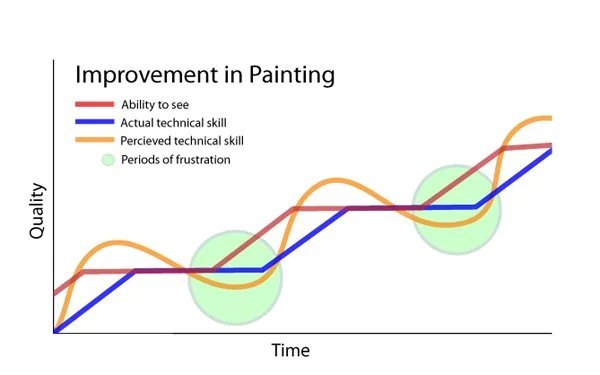

Marc Dalessio summarises the source of frustration in this graph.

The graph shows an example of perceived vs actual technical skill while learning to paint. In my opinion, it’s applicable to the act of learning anything.

Your actual technical skill is your objective ability to execute a task. Based on your practice, it’s the sign posts that say “you are capable of delivering on X”. X could be anything. MRR, piano grades, executing a certain trick.

There’s a tonne of ambiguity here, as it’s difficult to make anything absolute. There’s a reliance on these sorts of milestones to guide us along the way.

It can be assumed that actual ability can continuously improve—there is no such thing as perfection—yet it is clear that your ability will not and cannot develop linearly. In its most basic form, it’s just like learning a skill on The Sims, where the time spent to get to the next level exponentially increases as you progress.

Reality, however, is far more complicated than The Sim’s primitive skills system.

Some of this complexity is captured in your “ability to see”. I view this as your ability to think of what you want to achieve before you attempt it. It’s hearing the notes you want to play or seeing the pass before you play it.

Your actual ability, and ability to see are rarely in sync with each other. Imagine a cover band who nail every single note of every single song, but struggle to write their own songs. Or the writer, who knows the message they’re trying to convey, but doesn’t know which words to choose. As David Bayles and Ted Orland put it in Art & Fear, “vision is always ahead of execution”.

Perception complicates things further. Perception has played a key role in human survival. It’s the entry point to fight or flight mode. How we can see dangers before they arise. What it also means though is that our view of the world is ours, and ours alone.

Your perceived skill is just that. It’s a function of your current state which influences your understanding of your ability. It fluctuates as you practice, inline with your emotional response and your conditioning to respond to the events that unfold.

When you’re doing well, you’ll be welcomed by reward chemicals such as dopamine. Maybe that results in a state of overconfidence. Your perception starts to outrun your actual ability.

Make a mistake, and your perception drops. Make too many, and it’ll drop well below your actual. Confidence is perception, and without it, you may perform consistently below expectations.

In sports, the phrase “form is temporary, class is permanent” springs to mind. Where the individual in question may outperform their past selves for a period, or struggle to reach the heights of past performances.

This is where perceived ability and actual ability do not match. They try things they are incapable of (i.e., their perception is greater than their actual), or they don’t trust their ability so play within themselves (i.e., their perception is lower than their actual).

It highlights that our progress is a combination of actual ability, our perception, and our potential. And that frustration is caused when the three don’t line up as we expect.

It’s a pointer that something needs to change. The approach, the materials, or your expectations. Where one of these is inappropriate for your current ability. And now, as frustration builds, you can act and try something new.